From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

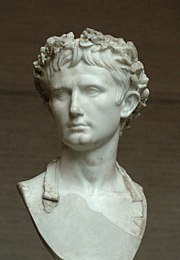

Augustus (Latin: IMPERATOR•CAESAR•DIVI•FILIVS•AVGVSTVS;a[›] September 23, 63 BC – August 19, AD 14), born Gaius Octavius Thurinus and prior to 27 BC, known as Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus after adoption (Latin: GAIVS•IVLIVS•CAESAR•OCTAVIANVS), was the first emperor of the Roman Empire, who ruled from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. The young Octavius was adopted by his great uncle, Julius Caesar, and came into his inheritance after Caesar's assassination in 44 BC. The following year, Octavian joined forces with Mark Antony and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus in a military dictatorship known as the Second Triumvirate. As a Triumvir, Octavian effectually ruled Rome and most of its provinces[1] as an autocrat, seizing consular power after the deaths of the consuls Hirtius and Pansa and having himself perpetually re-elected. The Triumvirate was eventually torn apart under the competing ambitions of its rulers: Lepidus was driven into exile, and Antony committed suicide following his defeat at the Battle of Actium by the armies of Octavian in 31 BC.

After the demise of the Second Triumvirate, Octavian restored the outward facade of the Roman Republic, with governmental power vested in the Roman Senate, but in practice retained his autocratic power. It took several years to work out the exact framework by which a formally republican state could be led by a sole ruler, the result of which became known as the Roman Empire. The emperorship was never an office like the Roman dictatorship which Caesar and Sulla had held before him; indeed, he declined it when the Roman populace "entreated him to take on the dictatorship".[2] By law, Augustus held a collection of powers granted to him for life by the Senate, including those of tribune, censor, and consul, without being formally elected to either of those (incompatible) offices. His substantive power stemmed from financial success and resources gained in conquest, the building of patronage relationships throughout the Empire, the loyalty of many military soldiers and veterans, the authority of the many honors granted by the Senate,[3] and the respect of the people. Augustus' control over the majority of Rome's legions established an armed threat that could be used against the Senate, allowing him to coerce the Senate's decisions. With his ability to eliminate senatorial opposition by means of arms, the Senate became docile towards his paramount position of leadership.

The rule of Augustus initiated an era of relative peace known as the Pax Romana, or Roman peace. Despite continuous frontier wars, and one year-long civil war over the imperial succession, the Mediterranean world remained at peace for more than two centuries. Augustus expanded the boundaries of the Roman Empire, secured the Empire's borders with client states, and made peace with Parthia through diplomacy. He reformed the Roman system of taxation, developed networks of roads with an official courier system, established a standing army (and a small navy), established the Praetorian Guard, and created official police and fire-fighting forces for Rome. Much of the city was rebuilt under Augustus; and he wrote a record of his own accomplishments, known as the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, which has survived. Upon his death in AD 14, Augustus was declared a god by the Senate, to be worshipped by the Romans.[4] His names Augustus and Caesar were adopted by every subsequent emperor, and the month of Sextilis was officially renamed August in his honour. He was succeeded by his stepson Tiberius.

Early life

-

While his paternal family was from the town of Velitrae, about 25 miles from Rome, Augustus was born in the city of Rome on September 23, 63 BC. He was born at Ox Heads, which was a small property on the Palatine Hill, very close to the Roman Forum. An astrologer had given a warning to his father. However, his father decided to keep the child despite the warning (rather than leave the child in the open to be eaten by dogs). He was given the name Gaius Octavius.[5] Due to the crowded nature of Rome at the time, Octavian (at this point he was simply called Gaius) was taken to his father's home village at Velitrae to be raised.

Octavian only mentions his father's family briefly in his memoirs, saying that he "came from a rich old equestrian family". His paternal great-grandfather was a military tribune in Sicily during the Second Punic War. His grandfather had served in several local political offices. His father, also named Gaius Octavius, had been governor of Macedonia.[6][7] Shortly after Octavius' birth, his father gave him the cognomen of Thurinus, possibly to commemorate his victory at Thurii over a rebellious band of slaves.[8] His mother Atia was the niece of Julius Caesar.

Since Octavius' father was a plebeian, Octavius himself was a plebeian, despite the fact that his mother, who was Julius Caesar's niece, was a patrician.[9] Octavius gained patrician status when he was adopted by Julius Caesar in 44 BC.

In 59 BC, when he was four years old, his father died.[10] His mother married a former governor of Syria, Lucius Marcius Philippus.[11] Philippus claimed descent from Alexander the Great, and was elected consul in 56 BC. Philippus never had much of an interest in young Octavius. Because of this, Octavius was raised by his grandmother (and Julius Caesar's sister), Julia Caesaris.

In 52 or 51 BC, Julia Caesaris died. Octavius delivered the funeral oration for his grandmother.[12] From this point, his mother and step-father took a more active role in raising him. He donned the toga virilis four years later,[13] and was elected to the College of Pontiffs in 47 BC.[14][15] The following year he was put in charge of the Greek games that were staged in honor of the Temple of Venus Genetrix, built by Julius Caesar.[15] According to Nicolaus of Damascus, Octavius wished to join Caesar's staff for his campaign in Africa but gave way when Atia protested.[16] In 46 BC, she consented for him to join Caesar in Hispania, where he planned to fight the forces of Pompey, Caesar's late enemy, but Octavius fell ill and was unable to travel.

When he had recovered, he sailed to the front, but was shipwrecked; after coming ashore with a handful of companions, he made it across hostile territory to Caesar's camp, which impressed his great-uncle considerably.[13] Velleius Paterculus reports that Caesar afterwards allowed the young man to share his carriage.[17] When back in Rome, Caesar deposited a new will with the Vestal Virgins, naming Octavius as the prime beneficiary.[18]

Rise to power

Heir to Caesar

At the time Caesar was killed on the Ides of March (the 15th) 44 BC, Octavius was studying and undergoing military training in Apollonia, Illyria. Rejecting the advice of some army officers to take refuge with the troops in Macedonia, he sailed to Italia to ascertain if he had any potential political fortunes or security.[19] After landing at Lupiae near Brundisium, he learned the contents of Caesar's will, and only then did he decide to become Caesar's political heir as well as heir to two-thirds of his estate.[20][19][15] Having no living legitimate children,[21] Caesar had adopted his great-nephew Octavius as his son and main heir.[22] Owing to his adoption, Octavius assumed the name Gaius Julius Caesar. Roman tradition dictated that he also append the cognomen Octavianus (Octavian) to indicate his biological family. Yet no evidence exists that he ever used that name, as it would have made his modest origins too obvious.[23][24] Mark Antony later charged that Octavian had earned his adoption by Caesar through sexual favours, though Suetonius describes Antony's accusation as political slander.[25]

To make a successful entry into the echelons of the Roman political hierarchy, Octavian could not rely on his limited funds.[26] After a warm welcome by Caesar's soldiers at Brundisium,[27] Octavian demanded a portion of the funds that were allotted by Caesar for the intended war against Parthia in the Middle East.[26] This amounted to 700 million sesterces stored at Brundisium, the staging ground in Italy for military operations in the east.[28] A later senatorial investigation into the disappearance of the public funds made no action against Octavian, since he subsequently used that money to raise troops against the Senate's arch enemy, Mark Antony.[27] Octavian made another bold move in 44 BC when he appropriated the annual tribute that had been sent from Rome's Near Eastern province to Italy without official permission.[24][29] Octavian began to bolster his personal forces with Caesar's veteran legionaries and with troops designated for the Parthian war, gathering support by emphasizing his status as heir to Caesar.[30][19] On his march to Rome through Italy, Octavian's presence and newly-acquired funds attracted many, winning over Caesar's former veterans stationed in Campania.[24] By June he had gathered an army of 3,000 loyal veterans, paying each a salary of 500 denarii.[31][32][33]

Arriving in Rome on May 6, 44 BC,[24] Octavian found the consul Mark Antony, Caesar's former colleague, in an uneasy truce with the dictator's assassins; they had been granted a general amnesty on March 17, yet Antony succeeded in driving most of them out of Rome.[24] This was due to his "inflammatory" eulogy given at Caesar's funeral, mounting public opinion against the assassins.[24] Although Mark Antony was amassing political support, Octavian still had opportunity to rival him as the leading member of the faction supporting Caesar. Mark Antony had lost the support of many Romans and supporters of Caesar when he at first opposed the motion to elevate Caesar to divine status.[34] Octavian failed to persuade Antony to relinquish Caesar's money to him, but managed to win support from Caesarian sympathizers during the summer.[35] In September, the Optimate orator Marcus Tullius Cicero began to attack Antony in a series of speeches, seeing Antony as the greatest threat to the order of the Senate.[36][37] With opinion in Rome turning against him and his year of consular power nearing its end, Antony attempted to pass laws which would lend him control over Cisalpine Gaul, which had been assigned as part of his province, from Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, one of Caesar's assassins.[38][39] Octavian meanwhile built up a private army in Italy by recruiting Caesarian veterans, and on November 28 won over two of Antony's legions with the enticing offer of monetary gain.[40][41][42] With Octavian's large and capable force, Antony saw the danger of staying in Rome, and to the relief of the Senate he fled to Cisalpine Gaul, which was to be handed to him on January 1.[42]

First conflict with Antony

After Decimus Brutus refused to give up Cisalpine Gaul, Antony besieged him at Mutina.[43] The resolutions passed by the Senate to stop the violence were rejected by Antony, as the Senate had no army of its own to challenge him; this provided an opportunity for Octavian, who was already known to have armed forces.[41] Cicero also defended Octavian against Antony's taunts about Octavian's lack of noble lineage; he stated "we have no more brilliant example of traditional piety among our youth."[44] This was in part a rebuttal to Antony's opinion of Octavian, as Cicero quoted Antony saying to Octavian, "You, boy, owe everything to your name".[45][46] In this unlikely alliance orchestrated by the arch anti-Caesarian senator Cicero, the Senate inducted Octavian as senator on January 1, 43 BC, yet he was also given the power to vote alongside the former consuls.[41][42] In addition, Octavian was granted imperium (commanding power), which made his command of troops legal, sending him to relieve the siege along with Hirtius and Pansa (the consuls for 43 BC).[47][41] In April of 43 BC, Antony's forces were defeated at the battles of Forum Gallorum and Mutina, forcing Antony to retreat to Transalpine Gaul. However, both consuls were killed, leaving Octavian in sole command of their armies.[48][49]

After heaping many more rewards on Decimus Brutus than Octavian for defeating Antony, the Senate attempted to give command of the consular legions to Decimus Brutus, yet Octavian decided not to cooperate.[50] Instead, Octavian stayed in the Po Valley and refused to aid any further offensive against Antony.[51] In July, an embassy of centurions sent by Octavian entered Rome and demanded that he receive the consulship left vacant by Hirtius and Pansa.[52] Octavian also demanded that the decree declaring Antony a public enemy should be rescinded.[51] When this was refused, he marched on the city with eight legions.[51] He encountered no military opposition in Rome, and on August 19, 43 BC was elected consul with his relative Quintus Pedius as co-consul.[53][54] Meanwhile, Antony formed an alliance with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, another leading Caesarian.[55]

Second Triumvirate

The Roman Revolution

Roman

aureus bearing the portraits of

Mark Antony (left) and Octavian (right), issued in 41 BC to celebrate the establishment of the

Second Triumvirate by Octavian, Antony and

Marcus Lepidus in 43 BC. Both sides bear the inscription "III VIR R P C", meaning "One of Three Men for the Regulation of the Republic".

[56]

In a meeting near Bologna in October of 43 BC, Octavian, Antony, and Lepidus formed a junta called the Second Triumvirate.[57] This explicit arrogation of special powers lasting five years was then supported by law passed by the plebs, unlike the unofficial First Triumvirate formed by Gnaeus Pompey Magnus, Julius Caesar and Marcus Licinius Crassus.[58][57] The triumvirs then set in motion proscriptions in which 300 senators and 2,000 equites were branded as outlaws and deprived of their property and, for those who failed to escape, their lives.[59] This decree issued by the triumvirate was motivated in part by a need to raise money to pay their troops' salaries for the upcoming conflict against Caesar's assassins, Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus.[60] Rewards for their arrest gave incentive for Romans to capture those proscribed, while the assets and properties of those arrested were seized by the triumvirs.[59] This measure by the triumvirs went beyond a simple purge of those allied with the assassins. Octavian objected to enacting the proscriptions at first because he wanted to spare the life of his newfound ally Marcus Tullius Cicero (who was to be listed on the proscriptions).[59] However, Antony's hatred of Cicero was unyielding, and Cicero fell victim to the occasion.[59] The death of so many republican senators allowed the triumvirs to fill their positions with their own supporters. This has been called the "Roman revolution" by twentieth-century historians; it had far-reaching implications in that it wiped out the old order and established a sturdy political foundation for the Augustan form of leadership to come.[61]

On January 1 42 BC, the Senate recognised Caesar as a divinity of the Roman state, "Divus Iulius". Octavian was able to further his cause by emphasizing the fact that he was Divi filius, "Son of God".[62] Antony and Octavian then sent 28 legions by sea to face the armies of Brutus and Cassius, who had built their base of power in Greece.[61] After two battles at Philippi in Macedonia in October of 42, the Caesarian army was victorious and Brutus and Cassius committed suicide. Mark Antony would later use the examples of these battles as a means to belittle Octavian, as both battles were decisively won with the use of Antony's forces.[63] In addition to claiming responsibility for both victories, Antony also branded Octavian as a coward for handing over his direct military control to Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa instead.[63]

After Philippi, a new territorial arrangement was made among the members of the Second Triumvirate. While Antony would leave Gaul, the provinces of Hispania, and Italia in the hands of Octavian, Antony traveled east to Egypt where he allied himself with Queen Cleopatra VII, the former lover of Julius Caesar and mother of Caesar's infant son, Caesarion. Lepidus was left with the province of Africa, stymied by Antony who conceded Hispania to Octavian instead.[64] Octavian was left to decide where in Italy to settle tens of thousands of veterans of the Macedonian campaign whom the triumvirs had promised to discharge. The tens of thousands who had fought on the republican side with Brutus and Cassius, who could easily ally with a political opponent of Octavian if not appeased, also required land.[64] There was no more government-controlled land to allot as settlements for their soldiers, so Octavian had to choose one of two options: alienating many Roman citizens by confiscating their land, or alienating many Roman soldiers who could mount a considerable opposition against him in the Roman heartland; Octavian chose the former.[65] There were as many as eighteen Roman towns affected by the new settlements, with entire populations driven out or at least given partial evictions.[66]

Rebellion and marriage alliances

A statue of Octavian, c. 30 BC.

Widespread dissatisfaction with Octavian over his soldiers' settlements encouraged many to rally at the side of Lucius Antonius, who was brother of Mark Antony and supported by a majority in the Senate.[66] Meanwhile, Octavian asked for a divorce from Clodia Pulchra, the daughter of Fulvia and her first husband Publius Clodius Pulcher. Claiming that his marriage with Clodia had never been consummated, he returned her to her mother, Mark Antony's wife. Fulvia decided to take action. Together with Lucius Antonius she raised an army in Italy to fight for Antony's rights against Octavian. However, Lucius and Fulvia took a political and martial gamble in opposing Octavian, since the Roman army still depended on the triumvirs for their salaries.[66] Lucius and his allies ended up in a defensive siege at Perusia (modern Perugia), where Octavian forced them into surrender in early 40 BC.[66] Lucius and his army were spared due to his kinship with Antony, the strongman of the East, while Fulvia was exiled to Sicyon.[67] However, Octavian showed no mercy for the mass of allies loyal to Lucius; on March 15, the anniversary of Julius Caesar's assassination, he had 300 Roman senators and equestrians executed for allying with Lucius.[68] Perusia was also pillaged and burned as a warning for others.[67] This bloody event somewhat sullied Octavian's career and was criticized by many, such as the Augustan poet Sextus Propertius.[68]

Sextus Pompeius, son of the first Triumvir and still a renegade general following Caesar's victory over Pompey, was established in Sicily and Sardinia as part of an agreement reached with the Second Triumvirate in 39 BC.[69] Both Antony and Octavian were vying for an alliance with Pompeius, who was ironically a member of the republican party, not the Caesarian faction.[68] Octavian succeeded in a temporary alliance when in 40 BC he married Scribonia, a daughter of Lucius Scribonius Libo who was a follower of Pompeius as well as his father-in-law.[68] Scribonia conceived Octavian's only natural child, Julia, who was born the same day that he divorced Scribonia to marry Livia Drusilla, little more than a year after his marriage.[68]

While in Egypt, Antony had been engaged in an affair with Cleopatra that produced three children, Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene II and Ptolemy Philadelphus. Aware of his deteriorating relationship with Octavian, Antony left Cleopatra; he sailed to Italy in 40 BC with a large force to oppose Octavian, laying siege to Brundisium. However, this new conflict proved untenable for both Octavian and Antony. Their centurions, who had become important figures politically, refused to fight due to their Caesarian cause, while the legions under their command followed suit.[70][71] Meanwhile in Sicyon, Antony's wife Fulvia died of a sudden illness while Antony was en route to meet her. Fulvia's death and the mutiny of their centurions allowed the two remaining triumvirs to effect a reconciliation.[70][71] In the autumn of 40, Octavian and Antony approved the Treaty of Brundisium, by which Lepidus would remain in Africa, Antony in the East, Octavian in the West. The Italian peninsula was left open to all for the recruitment of soldiers, but in reality, this provision was useless for Antony in the East.[70] To further cement relations of alliance with Mark Anthony, Octavian gave his sibling sister, Octavia Minor, in marriage to Anthony in late 40 BC.[70] During their marriage, Octavia gave birth to two daughters (known as Antonia Major and Antonia Minor).

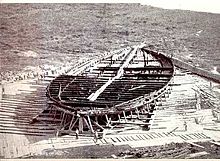

War with Pompeius

Sextus Pompeius threatened Octavian in Italy by denying to the peninsula shipments of grain through the Mediterranean; Pompeius' own son was put in charge as naval commander in the effort to cause widespread famine in Italy.[71] Pompeius' control over the sea prompted him to take on the name Neptuni filius, "son of Neptune."[72] A temporary peace agreement was reached in 39 with the treaty of Misenum; the blockade on Italy was lifted once Octavian granted Pompeius Sardinia, Corsica, Sicily, the Peloponnese, and an ensured future position as consul for the year 35.[72][71] The territorial agreement amongst the triumvirs and Sextus Pompeius began to crumble once Octavian divorced Scribonia and married Livia on January 17, 38 BC.[73] One of Pompeius' naval commanders betrayed him and handed over Corsica and Sardinia to Octavian; however, Octavian needed Antony's support to attack Pompeius, so an agreement was reached with the Second Triumvirate's extension for another five-year period beginning in 37.[74][75] Antony in supporting Octavian expected to gain support for his own campaign against Parthia, desiring to avenge Rome's defeat at Carrhae in 53.[75] In an agreement reached at Tarentum, Antony provided 120 ships for Octavian to use against Pompeius, while Octavian was to send 20,000 legionaries to Antony for use against Parthia.[76] However, Octavian sent only a tenth the number of those promised, an intentional provocation that Antony would not forget six years later when they faced each other in battle.[76]

Octavian and Lepidus launched a joint operation against Sextus in Sicily in 36.[77] Despite setbacks for Octavian, the naval fleet of Sextus Pompeius was almost entirely destroyed on September 3, 36 BC by general Agrippa at the naval battle of Naulochus.[78] Sextus fled with his remaining forces to the east, where he was captured and executed in Miletus by one of Antony's generals the following year.[78] Both Lepidus and Octavian gathered the surrendered troops of Pompeius, yet Lepidus felt empowered enough to claim Sicily for himself, ordering Octavian to leave.[78] However, Lepidus' troops deserted him and defected to Octavian since they were weary of fighting and found Octavian's promises of money to be enticing.[78] Lepidus surrendered to Octavian and was permitted to retain the office of pontifex maximus (head of the college of priests), but was ejected from the Triumvirate, his public career at an end, and was effectively exiled to a villa at Cape Circei in Italy.[79][78] The Roman dominions were now divided between Octavian in the West and Antony in the East. To maintain peace and stability in his portion of the Empire, Octavian ensured Rome's citizens of their rights to property. This time he settled his discharged soldiers outside of Italy while returning 30,000 slaves to former Roman owners that had previously fled to Pompeius to join his army and navy.[80] To ensure his own safety and that of Livia and Octavia once he returned to Rome, Octavian had the Senate grant him, his wife, and his sister tribunal immunity, or sacrosanctitas.[81]

War with Antony

-

Meanwhile, Antony's campaign against Parthia turned disastrous, tarnishing his image as a leader, while the mere 2,000 legionaries sent by Octavia to Antony was hardly enough to replenish his forces.[82] On the other hand, Cleopatra could restore his army to full strength, and since he was already engaged in a romantic affair with her, he decided to send Octavia back to Rome.[83] Although Antony had the interests of rebuilding his military in mind, this act played right into the hands of Octavian, who spread propaganda implying that Antony was becoming less than Roman because he rejected a legitimate Roman spouse for an "Oriental paramour".[84] In 36 BC, Octavian used a political ploy to make himself look less autocratic and Antony more the villain by proclaiming that the civil wars were coming to an end, and that he would step down as triumvir if only Antony would do the same; Antony refused.[85] After Roman troops captured Armenia in 34 BC, Antony made his son Alexander Helios the ruler of Armenia; he also awarded the title "Queen of Kings" to Cleopatra, acts which Octavian used to convince the Roman Senate that Antony had ambitions to diminish the preeminence of Rome.[84] When Octavian became consul once again on January 1, 33 BC, he opened the following session in the Senate with a vehement attack on Antony's grants of titles and territories to his relatives and to his queen.[86] Defecting consuls and senators rushed over to the side of Antony in disbelief of the propaganda (which turned out to be true), yet so did able ministers desert Antony for Octavian in the autumn of 32 BC.[87] These defectors, Munatius Plancus and Marcus Titius, gave Octavian the information he needed to confirm with the Senate all the accusations he made against Antony.[88] By storming the sanctuary of the Vestal Virgins, Octavian forced their chief priestess to hand over Antony's secret will, which would have given away Roman-conquered territories as kingdoms for his sons to rule, alongside plans to build a tomb in Alexandria for him and his queen to reside upon their deaths.[89][90] In late 32 BC, the Senate officially revoked Antony's powers as consul and declared war on Cleopatra's regime in Egypt.[91][92]

The Battle of Actium, by Lorenzo Castro, painted 1672, National Maritime Museum, London.

Octavian gained a preliminary victory in early 31 BC when the navy under command of Agrippa successfully ferried their troops across the Adriatic Sea.[93] While Agrippa cut off Antony and Cleopatra's main force from their supply routes at sea, Octavian landed on the mainland opposite the island of Corcyra (modern Corfu) and marched south.[93] Trapped on land and sea, deserters of Antony's army fled to Octavian's side daily while Octavian's forces were comfortable enough to make preparations.[93] In a desperate attempt to break free of the naval blockade, Antony's fleet sailed through the bay of Actium on the western coast of Greece. It was there that Antony's fleet faced the much larger fleet of smaller, more maneuverable ships under commanders Agrippa and Gaius Sosius in the battle of Actium on September 2, 31 BC.[94] Antony and his remaining forces were only spared due to a last-ditch effort by Cleopatra's fleet that had been waiting nearby.[95] Octavian pursued them, and after another defeat in Alexandria on August 1, 30 BC, Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide; Antony fell on his own sword and into Cleopatra's arms, while she let a poisonous snake bite her.[96] Having exploited his position as Caesar's heir to further his own political career Octavian was only too well aware of the dangers in allowing another to do so and, reportedly commenting that "two Caesars are one too many", he ordered Caesarion to be killed whilst sparing Cleopatra's children by Antony.[97][98]

Although his methods were cruel, it was Mark Antony who flaunted the child as the legitimate heir of the deified Julius Caesar, hence weakening the credibility of Octavian to hold that entitlement legitimately.[99] Octavian had previously shown little mercy to military combatants and acted in ways that had proven unpopular with the Roman people, yet he was given credit for pardoning many of his opponents after the Battle of Actium.[100]

Octavian becomes Augustus

After Actium and the defeat of Antony and Cleopatra, Octavian was in a position to rule the entire Republic under an unofficial principate.[101] However, Octavian would have to achieve this through incremental gaining of power, courting the Senate and people, while upholding republican traditions of Rome to appear that he was not aiming for dictatorship or monarchy.[102][103] Marching into Rome, Octavian and Marcus Agrippa were elected as dual consuls by the Senate.[104] Years of civil war had left Rome in a state of near-lawlessness, but the Republic was not prepared to accept the control of Octavian as a despot. At the same time, Octavian could not simply give up his authority without risking further civil wars amongst the Roman generals, and even if he desired no position of authority whatsoever, his position demanded that he look to the well-being of the city of Rome and the Roman provinces. Octavian's aims from this point forward were to return Rome to a state of stability, traditional legality, and civility by lifting the overt political pressure imposed upon the courts of law and ensuring free elections, in name at least.[105]

First settlement

Augustus as a magistrate; the statue's marble head was made c. 30–20 BC, the body sculpted in the 2nd century AD.

In 27 BC, Octavian formally returned full power to the Roman Senate and relinquished his control of the Roman provinces and their armies.[104] However, under the consulship of Octavian, the Senate had little power in initiating legislation by introducing bills for senatorial debate.[104] Although Octavian was no longer in direct control of the provinces and their armies, he retained the loyalty of active duty soldiers and veterans alike.[104] The careers of many clients and adherents depended on his patronage, as his financial power in the Roman Republic was unrivaled.[104] The historian Werner Eck states of Augustus:

| “ |

The sum of his power derived first of all from various powers of office delegated to him by the Senate and people, secondly from his immense private fortune, and thirdly from numerous patron-client relationships he established with individuals and groups throughout the Empire. All of them taken together formed the basis of his auctoritas, which he himself emphasized as the foundation of his political actions.[106] |

” |

To a large extent, the public was aware of the vast financial resources Augustus commanded. When Augustus failed to encourage enough senators to finance the building and maintenance of networks of roads in Italy, he took over direct responsibility of building roads in 20 BC.[107] His construction of roads was publicized on the Roman currency issued in 16 BC, after he donated vast amounts of money to the aerarium Saturni, the public treasury.[107]

According to Scullard, however, Augustus' power was based on the exercise of "…a predominant military power and that the ultimate sanction of his authority was force, however much the fact was disguised."[108]

The Senate proposed to Octavian, the cherished victor of Rome's civil wars, to once again assume command of the provinces. The senate proposal was a ratification of Octavian's extra-constitutional power. Through the senate, Octavian was able to continue the appearance of a still-functional constitution of the Roman Republic. Whilst putting on the appearance of reluctance he accepted a ten year responsibility of overseeing provinces that were considered to be in a somewhat chaotic state.[109][110] The provinces ceded to him to pacify within the promised ten year period comprised much of the conquered Roman world, including all of Hispania and Gaul, Syria, Cilicia, Cyprus, and Egypt.[109][111] Moreover, command over these provinces provided Octavian with control over the majority of Rome's legions.[111][112] While Octavian acted as consul in Rome, he dispatched senators to the provinces under his command as his representatives to manage provincial affairs and ensure his orders were carried out.[112] On the other hand, the provinces not under Octavian's control were overseen by governors chosen by the Roman Senate.[112] Octavian became the most powerful political figure in the city of Rome and in most of its provinces, yet he did not have a sole monopoly on political and martial power.[113] The Senate still controlled North Africa, an important regional producer of grain, as well as Illyria and Macedonia, two martially strategic regions with several legions.[113] However, with control of only five or six legions distributed amongst three senatorial proconsuls, compared to the 20 legions under the control of Augustus, the Senate's control of these regions did not amount to any political or martial challenge to Octavian.[102][114] The Senate's control over some of the Roman provinces helped maintain a republican facade for the autocratic Principate.[102] Also, Octavian's control of entire provinces for the objective of securing peace and creating stability followed a Republican era precedence, with prominent Romans such as Pompey being granted similar military powers in times of crisis and instability.[102]

In January of 27 BC, the Senate gave Octavian the new titles of Augustus and Princeps.[115] Augustus, from the Latin word Augere (meaning to increase), can be translated as "the illustrious one".[100] It was a title of religious rather than political authority.[100] According to Roman religious beliefs, the title symbolized a stamp of authority over humanity—and in fact nature—that went beyond any constitutional definition of his status. After the harsh methods employed in consolidating his control, the change in name would also serve to demarcate his benign reign as Augustus from his reign of terror as Octavian. His new title of Augustus was also more favorable than Romulus, the previous one he styled for himself in reference to the story of Romulus and Remus (founders of Rome), which would symbolize a second founding of Rome.[100] However, the title of Romulus was associated too strongly with notions of monarchy and kingship, an image Octavian tried to avoid.[100] Princeps, comes from the Latin phrase primum caput, "the first head", originally meaning the oldest or most distinguished senator whose name would appear first on the senatorial roster; in the case of Augustus it became an almost regnal title for a leader who was first in charge.[116][3] Princeps had also been a title under the Republic for those who had served the state well; for example, Pompey had held the title. Augustus also styled himself as Imperator Caesar divi filius, "Commander Caesar son of the deified one".[115] With this title he not only boasted his familial link to deified Julius Caesar, but the use of Imperator signified a permanent link to the Roman tradition of victory.[115] The word Caesar was merely a cognomen for one branch of the Julian family, yet Augustus transformed Caesar into a new family line that began with him.[115]

Augustus was granted the right to hang the corona civica, the "civic crown" made from oak, above his door and have laurels drape his doorposts.[113] This crown was usually held above the head of a Roman general during a triumph, with the individual holding the crown charged to continually repeat "memento mori", or, "Remember, you are mortal", to the triumphant general. Additionally, laurel wreaths were important in several state ceremonies, and crowns of laurel were rewarded to champions of athletic, racing, and dramatic contests. Thus, both the laurel and the oak were integral symbols of Roman religion and statecraft; placing them on Augustus's doorposts was tantamount to declaring his home the capital. However, Augustus renounced flaunting insignia of power such as holding a scepter, wearing a diadem, or wearing the golden crown and purple toga of his predecessor Julius Caesar.[117] If he refused to symbolize his power by donning and bearing these items on his person, the Senate nonetheless awarded him with a golden shield displayed in the meeting hall of the Curia, bearing the inscription virtus, pietas, clementia, iustitia—"valor, piety, clemency, and justice."[113][3]

Second settlement

In 23 BC, there was a political crisis that involved Augustus' co-consul Terentius Varro Murena, who was part of a conspiracy against Augustus. The exact details of the conspiracy are unknown, yet Murena did not serve a full term as consul before Calpurnius Piso was elected to replace him.[118][119] Piso was a well known member of the republican faction, and serving as co-consul with him was another means by Augustus to show his willingness to make concessions and cooperate with all political parties.[120] In the late spring Augustus suffered a severe illness, and on his supposed deathbed made arrangements that would put in doubt the senators' suspicions of his anti-republicanism.[118][121] Augustus prepared to hand down his signet ring to his favored general Agrippa.[118][121] However, Augustus handed over to his co-consul Piso all of his official documents, an account of public finances, and authority over listed troops in the provinces while Augustus' supposedly favored nephew Marcus Claudius Marcellus came away empty-handed.[118][121] This was a surprise to many who believed Augustus would have named an heir to his position as an unofficial emperor.[122] Augustus bestowed only properties and possessions to his designated heirs, as a system of institutionalized imperial inheritance would have provoked resistance and hostility amongst the republican-minded Romans fearful of monarchy.[103]

Soon after his bout of illness subsided, Augustus gave up his permanent consulship.[121] The only other times Augustus would serve as consul would be in the years 5 and 2 BC.[121][123] Although he had resigned as consul, Augustus retained his consular imperium, leading to a second compromise between him and the Senate known as the Second Settlement.[124] This was a clever ploy by Augustus; by stepping down as one of two consuls, this allowed aspiring senators a better chance to fill that position, while at the same time Augustus could "exercise wider patronage within the senatorial class."[125] Augustus was no longer in an official position to rule the state, yet his dominant position over the Roman provinces remained unchanged as he became a proconsul.[121][126] As an earlier consul he had the power to intervene, when he deemed necessary, with the affairs of provincial proconsuls appointed by the Senate.[127] As a proconsul Augustus did not want this authority of overriding provincial governors to be stripped from him, so imperium proconsulare maius, or "power over all the proconsuls" was granted to Augustus by the Senate.[124]

Augustus was also granted the power of a tribune (tribunicia potestas) for life, though not the official title of tribune.[124] Legally it was closed to patricians, a status that Augustus had acquired years ago when adopted by Julius Caesar.[125] This allowed him to convene the Senate and people at will and lay business before it, veto the actions of either the Assembly or the Senate, preside over elections, and the right to speak first at any meeting.[123][128] Also included in Augustus' tribunician authority were powers usually reserved for the Roman censor; these included the right to supervise public morals and scrutinize laws to ensure they were in the public interest, as well as the ability to hold a census and determine the membership of the Senate.[129] With the powers of a censor, Augustus appealed to virtues of Roman patriotism by banning all other attire besides the classic toga while entering the Forum.[130] There was no precedent within the Roman system for combining the powers of the tribune and the censor into a single position, nor was Augustus ever elected to the office of censor.[131] Julius Caesar had been granted similar powers, wherein he was charged with supervising the morals of the state, however this position did not extend to the censor's ability to hold a census and determine the Senate's roster. The office of the tribune plebis began to lose its prestige due to Augustus' amassing of tribunal powers, so he revived its importance by making it a mandatory appointment for any plebeian desiring the praetorship.[132]

In addition to tribunician authority, Augustus was granted sole imperium within the city of Rome itself: all armed forces in the city, formerly under the control of the prefects and consuls, were now under the sole authority of Augustus.[133] With maius imperium proconsulare, Augustus was the only individual able to receive a triumph as he was ostensibly the head of every Roman army.[134] In 19 BC, Lucius Cornelius Balbus, governor of Africa who defeated the Garamantes, was the first man of provincial origin to receive this award, as well as the last.[134] For every following Roman victory the credit was given to Augustus, due to the fact that Rome's armies were commanded by the legatus, who were deputies of the princeps in the provinces.[134] Augustus' eldest son by marriage to Livia, Tiberius, was the only exception to this rule when he received a triumph for victories in Germania in 7 BC.[135] Ensuring that his status of maius imperium proconsulare was renewed in 13 BC, Augustus stayed in Rome during the renewal process and provided veterans with lavish donations to gain their support.[123]

Many of the political subtleties of the Second Settlement seem to have evaded the comprehension of the Plebeian class. When Augustus failed to stand for election as consul in 22 BC, fears arose once again that Augustus was being forced from power by the aristocratic Senate. In 22, 21, and 19 BC, the people rioted in response, and only allowed a single consul to be elected for each of those years, ostensibly to leave the other position open for Augustus.[136] In 22 BC there was a food shortage in Rome which sparked panic, while many urban plebs called for Augustus to take on dictatorial powers to personally oversee the crisis.[123] After a theatrical display of refusal before the Senate, Augustus finally accepted authority over Rome's grain supply "by virtue of his proconsular imperium", and ended the crisis almost immediately.[123] It was not until AD 8 that a food crisis of this sort prompted Augustus to establish a praefectus annonae, a permanent prefect who was in charge of procuring food supplies for Rome.[137] In 19 BC, the Senate voted to allow Augustus to wear the consul's insignia in public and before the Senate,[133] as well as sit in the symbolic chair between the two consuls and hold the fasces, an emblem of consular authority.[138] Like his tribune authority, the granting of consular powers to him was another instance of holding power of offices he did not actually hold.[138] This seems to have assuaged the populace; regardless of whether or not Augustus was actually a consul, the importance was that he appeared as one before the people. On March 6, 12 BC, after the death of Lepidus, he additionally took up the position of pontifex maximus, the high priest of the collegium of the Pontifices, the most important position in Roman religion.[139][140] On February 5, 2 BC, Augustus was also given the title pater patriae, or "father of the country".[141][142]

Later Roman Emperors would generally be limited to the powers and titles originally granted to Augustus, though often, to display humility, newly-appointed Emperors would often decline one or more of the honorifics given to Augustus. Just as often, as their reign progressed, Emperors would appropriate all of the titles, regardless of whether they had actually been granted them by the Senate. The civic crown, which later Emperors took to actually wearing, consular insignia, and later the purple robes of a Triumphant general (toga picta) became the imperial insignia well into the Byzantine era.

War and expansion under Augustus

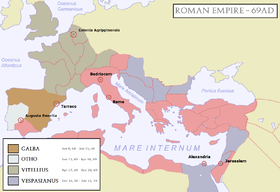

Extent of the Roman Empire under Augustus; the yellow legend represents the extent of the Empire in

31 BC, the shades of green represent gradually conquered territories under the reign of Augustus, and pink areas on the map represent

client states.

- Further information: Roman relations with the Parthians and Sassanids

Imperator Caesar Divi Filius Augustus chose Imperator, "victorious commander" to be his first name, since he wanted to make the notion of victory associated with him emphatically clear.[143] By the year 13, Augustus boasted 21 occasions where his troops proclaimed imperator as his title after a successful battle.[143] Almost the entire fourth chapter in his publicly-released memoirs of achievements known as the Res Gestae was devoted to his military victories and honors.[143] Pandering to Roman patriots, Augustus promoted the ideal of a superior Roman civilization with a task of ruling the world (the extent to which the Romans knew it), embodied in the phrase tu regere imperio populos, Romane, memento—"Roman, remember by your strength to rule the earth's peoples!"[130] This fit well with the Roman elite and the wider public opinion of the day which favored expansionism, reflected in a statement by the famous Roman poet Virgil who said that the gods had granted Rome imperium sine fine, "sovereignty without limit".[144] There was public disappointment and regret for not avenging Crassus' captured battle standards when Augustus decided that the Middle Eastern power of Parthia should not be invaded.[145] However, there were many other viable lands to be conquered.

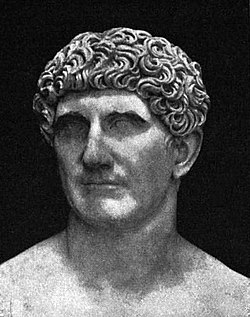

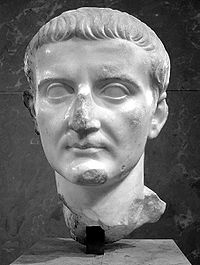

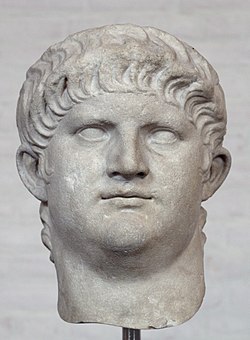

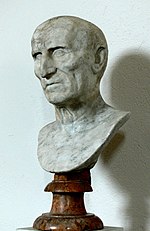

Bust of

Tiberius, a successful military commander under Augustus before he was designated as his heir and successor.

By the end of his reign, the armies of Augustus had conquered northern Hispania (modern Spain and Portugal),[146] the Alpine regions of Raetia and Noricum (modern Switzerland, Bavaria, Austria, Slovenia),[146] Illyricum and Pannonia (modern Albania, Croatia, Hungary, Serbia, etc.),[146] and extended the borders of the Africa Province to the east and south.[146] After the reign of the client king Herod the Great (73–4 BC), Judea was added to the province of Syria when Augustus deposed his successor Herod Archelaus.[146] Like Egypt which had been conquered after the defeat of Antony in 30 BC, Syria was governed not by a proconsul or legate of Augustus, but a high prefect of the equestrian class.[146] Again, no military effort was needed in 25 BC when Galatia (modern Turkey) was converted to a Roman province shortly after Amyntas of Galatia was killed by an avenging widow of a slain prince from Homonada.[146] When the rebellious tribes of Cantabria in modern-day Spain were finally quelled in 19 BC, the territory fell under the provinces of Hispania and Lusitania.[147] This region proved to be a major asset in funding Augustus' future military campaigns, as it was rich in mineral deposits that could be fostered in Roman mining projects.[147] Conquering the peoples of the Alps in 16 BC was another important victory for Rome since it provided a large territorial buffer between the Roman citizens of Italy and Rome's enemies in Germania to the north.[148] The poet Horace dedicated an ode to the victory, while the monument Trophy of Augustus near Monaco was built to honor the occasion.[149] The capture of the Alpine region also served the next offensive in 12 BC, when Tiberius began the offensive against the Pannonian tribes of Illyricum and his brother Nero Claudius Drusus against the Germanic tribes of the eastern Rhineland.[150] Both campaigns were successful, as Drusus' forces reached the Elbe River by 9 BC, yet he died shortly after by falling off his horse.[150] It was recorded that the pious Tiberius walked in front of his brother's body all the way back to Rome.[151]

To protect the eastern areas of the Empire from the Parthian threat, Augustus relied on the client states of the east to act as territorial buffers and areas which could raise their own troops for defense.[152] To ensure security of the Empire's eastern flank, Augustus stationed a Roman army in Syria just in case, while his skilled stepson Tiberius negotiated with the Parthians as Rome's diplomat to the East.[152] One of Tiberius' greatest diplomatic achievements was negotiating for the return of Crassus' battle standards, a symbolic victory and great boost of morale for Rome.[152][151] Tiberius was also responsible for restoring Tigranes V to the throne of Armenia.[151]

Although Parthia always posed a threat to Rome in the east, the real battlefront was along the Rhine and Danube rivers.[152] Before the final fight with Antony, Octavian's campaigns against the tribes in Dalmatia was the first step in expanding Roman dominions to the Danube.[153] Victory in battle was not always a permanent success, as newly conquered territories were constantly retaken by Rome's enemies in Germania.[152] A prime example of Roman loss in battle was the Battle of Teutoburg Forest in AD 9, where three out of nine legions led by Publius Quinctilius Varus were destroyed with few survivors by Arminius, leader of the Cherusci.[154] Augustus retaliated by dispatching Tiberius and Drusus to the Rhineland to pacify it, which was a huge success in AD 13.[155][156] The Roman general Germanicus took advantage of a Cherusci civil war between Arminius and Segestes; they defeated Arminius, who fled that battle but was killed later in 19 due to treachery.[157]

Death and succession

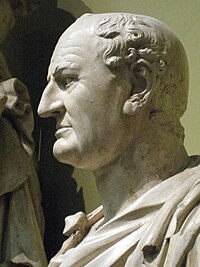

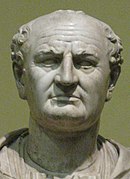

Roman

aureus struck under Augustus,

c. AD 13–14. The reverse shows

Tiberius riding on a

quadriga, celebrating the fifteenth renewal of his tribunician power. At least six potential heirs, including Agrippa and his sons, had expired or proven incapable of succeeding Augustus, before he finally settled on Tiberius in AD 9.

The illness of Augustus in 23 BC brought the problem of succession to the forefront of political issues and the public. To ensure stability, he needed to designate an heir to his unique position in Roman society and government. This was to be achieved in small, undramatic, and incremental ways that did not stir senatorial fears of monarchy.[158] If someone was to succeed his unofficial position of power, they were going to have to earn it through their own publicly-known merits.[158] Some Augustan historians argue that indications pointed toward his sister's son Marcellus, who had been quickly married to Augustus' daughter Julia the Elder.[159] Other historians dispute this due to Augustus' will read aloud to the Senate while he was seriously ill in 23 BC,[160] instead indicating a preference for Marcus Agrippa, who was Augustus' second in charge and arguably the only one of his associates who could have controlled the legions and held the Empire together.[161] After the death of Marcellus in 23 BC, Augustus married his daughter to Agrippa. This union produced five children, three sons and two daughters: Gaius Caesar, Lucius Caesar, Vipsania Julia, Agrippina the Elder, and Postumus Agrippa, so named because he was born after Marcus Agrippa died. Shortly after the Second Settlement, Agrippa was granted a five-year term of administering the eastern half of the Empire with the imperium of a proconsul and the same tribunicia potestas granted to Augustus (although not trumping Augustus' authority), his seat of governance stationed at Samos in the Cyclades.[162][161] Although this granting of power would have shown Augustus' favor for Agrippa, it was also a measure to please members of his Caesarian party by allowing one of their members to share a considerable amount of power with him.[162]

Augustus' intent to make Gaius and Lucius Caesar his heirs was apparent when he adopted them as his own children, and personally ushered them into their political careers by serving as consul with each in 5 and 2 BC.[121] Augustus also showed favor to his stepsons, Livia's children from her first marriage, Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus and Tiberius Claudius, granting them military commands and public office, and seeming to favor Drusus. However, Drusus' marriage to Antonia, Augustus' niece, was a relationship far too embedded within the family to disturb over succession issues.[163] After Agrippa died in 12 BC, Livia's son Tiberius was ordered to divorce his own wife Vipsania and marry Agrippa's widow, Augustus' daughter Julia—as soon as a period of mourning for Agrippa had ended.[163] While Drusus' marriage to Antonia was considered an unbreakable affair, Vipsania was "only" the daughter of the late Agrippa from his first marriage.[163]

Tiberius shared in Augustus' tribune powers as of 6 BC, but shortly thereafter went into retirement, reportedly wanting no further role in politics while he exiled himself to Rhodes.[135][164] Although no specific reason is known for his departure, it could have been a culmination of reasons, including a failing marriage with Julia.[135][164] It could very well have been from feelings of jealousy and being left out since Augustus' young grandchildren-turned-sons, Gaius and Lucius, joined the college of priests at an early age, were presented to spectators in a more favorable light, and were introduced to the army in Gaul.[165][166] After the early deaths of both Lucius and Gaius in AD 2 and 4 respectively, and the earlier death of his brother Drusus (9 BC), Tiberius was recalled to Rome in June AD 4, where he was adopted by Augustus on the condition that he, in turn, adopt his nephew Germanicus.[167] This continued the tradition of presenting at least two generations of heirs.[163] In that year, Tiberius was also granted the powers of a tribune and proconsul, emissaries from foreign kings had to pay their respects to him, and by 13 was awarded with his second triumph and equal level of imperium with that of Augustus.[168] The only other possible claimant as heir was Postumus Agrippa, who had been exiled by Augustus in AD 7, his banishment made permanent by senatorial decree, and Augustus officially disowned him.[169] He certainly fell out of Augustus' favor as an heir; historian Erich S. Gruen notes various contemporary sources that state Postumus Agrippa was a "vulgar young man, brutal and brutish, and of depraved character."[169]

On August 19 AD 14, Augustus died while visiting the place of his father's death at Nola, and Tiberius—who was present alongside Livia at Augustus' deathbed—was named his heir.[170] Augustus' famous last words were, "Did you like the performance?"—referring to the play-acting and regal authority that he had put on as emperor. An enormous funerary procession of mourners traveled with Augustus' body from Nola to Rome, and on the day of his burial all public and private businesses closed for the day.[170] Tiberius and his son Drusus delivered the eulogy while standing atop two rostra.[4] Augustus' body inside a coffin was cremated on a pyre close to his mausoleum, and it was proclaimed that Augustus joined the company of the gods as a member of the Roman pantheon.[4] In 410 during the Sack of Rome the mausolem was despoiled by the Goths and his ashes scattered.

Augustus' legacy

- Further information: Augustus in popular culture

Augustus' reign laid the foundations of a regime that lasted hundreds of years until the ultimate decline of the Roman Empire. Both his borrowed surname, Caesar, and his title Augustus became the permanent titles of the rulers of Roman Empire for fourteen centuries after his death, in use both at Old Rome and New Rome. In many languages, caesar became the word for emperor, as in the German Kaiser and in the Bulgarian and subsequently Russian Tsar. The cult of Divus Augustus continued until the state religion of the Empire was changed to Christianity in 391 by Theodosius I. Consequently, there are many excellent statues and busts of the first emperor. He had composed an account of his achievements, the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, to be inscribed in bronze in front of his mausoleum.[171] Copies of the text were inscribed throughout the Empire upon his death.[172] The inscriptions in Latin featured translations in Greek beside it, and were inscribed on many public edifices, such as the temple in Ankara dubbed the Monumentum Ancyranum, called the "queen of inscriptions" by historian Theodor Mommsen.[173] There are a few other written works by Augustus that have not survived. This includes his poems Sicily, Epiphanus, and Ajax, an autobiography of 13 books, a philosophical treatise, and his written rebuttal to Brutus' Eulogy of Cato.[174]

Many consider Augustus to be Rome's greatest emperor; his policies certainly extended the Empire's life span and initiated the celebrated Pax Romana or Pax Augusta. He was intelligent, decisive, and a shrewd politician, but he was not perhaps as charismatic as Julius Caesar, and was influenced on occasion by his third wife, Livia (sometimes for the worse). Nevertheless, his legacy proved more enduring. The city of Rome was utterly transformed under Augustus, with Rome's first institutionalized police force, fire fighting force, and the establishment of the municipal prefect as a permanent office.[175] The police force was divided into cohorts of 500 men each, while the units of firemen ranged from 500 to 1,000 men each, with 7 units assigned to 14 divided city sectors.[175] A praefectus vigilum, or "Prefect of the Watch" was put in charge of the vigiles, Rome's fire brigade and police.[176] With Rome's civil wars at an end, Augustus was also able to create a standing army for the Roman Empire, fixed at a size of 28 legions of about 170,000 soldiers.[177] This was supported by numerous auxiliary units of 500 soldiers each, often recruited from recently conquered areas.[178] With his finances securing the maintenance of roads throughout Italy, Augustus also installed an official courier system of relay stations overseen by a military officer known as the praefectus vehiculorum.[179] Besides the advent of swifter communication amongst Italian polities, his extensive building of roads throughout Italy also allowed Rome's armies to march swiftly and at an unprecedented pace across the country.[180] In the year 6 Augustus established the aerarium militare, donating 170 million sesterces to the new military treasury that provided for both active and retired soldiers.[181] One of the most lasting institutions of Augustus was the establishment of the Praetorian Guard in 27 BC, originally a personal bodyguard unit on the battlefield that evolved into an imperial guard as well as an important political force in Rome.[182] They had the power to intimidate the Senate, install new emperors, and depose ones they disliked; the last emperor they served was Maxentius, as it was Constantine I who disbanded them in the early 4th century and destroyed their barracks, the Castra Praetoria.[183]

Although the most powerful individual in the Roman Empire, Augustus wished to embody the spirit of Republican virtue and norms. He also wanted to relate to and connect with the concerns of the plebs and lay people. He achieved this through various means of generosity and a cutting back of lavish excess. In the year 29 BC, Augustus paid 400 sesterces each to 250,000 citizens, 1,000 sesterces each to 120,000 veterans in the colonies, and spent 700 million sesterces in purchasing land for his soldiers to settle upon.[184] He also restored 82 different temples to display his care for the Roman pantheon of deities.[184] In 28 BC, he melted down 80 silver statues erected in his likeness and in honor of him, an attempt of his to appear frugal and modest.[184]

The longevity of Augustus' reign and its legacy to the Roman world should not be overlooked as a key factor in its success. As Tacitus wrote, the younger generations alive in AD 14 had never known any form of government other than the Principate.[185] Had Augustus died earlier (in 23 BC, for instance), matters might have turned out differently. The attrition of the civil wars on the old Republican oligarchy and the longevity of Augustus, therefore, must be seen as major contributing factors in the transformation of the Roman state into a de facto monarchy in these years. Augustus' own experience, his patience, his tact, and his political acumen also played their parts. He directed the future of the Empire down many lasting paths, from the existence of a standing professional army stationed at or near the frontiers, to the dynastic principle so often employed in the imperial succession, to the embellishment of the capital at the emperor's expense. Augustus' ultimate legacy was the peace and prosperity the Empire enjoyed for the next two centuries under the system he initiated. His memory was enshrined in the political ethos of the Imperial age as a paradigm of the good emperor. Every emperor of Rome adopted his name, Caesar Augustus, which gradually lost its character as a name and eventually became a title.[4]

Revenue reforms

Coin of the

Himyarite Kingdom, southern coast of the

Arabian peninsula. This is also an imitation of a coin of Augustus. 1st century.

Augustus's public revenue reforms had a great impact on the subsequent success of the Empire. Augustus brought a far greater portion of the Empire's expanded land base under consistent, direct taxation from Rome, instead of exacting varying, intermittent, and somewhat arbitrary tributes from each local province as Augustus's predecessors had done.[186] This reform greatly increased Rome's net revenue from its territorial acquisitions, stabilized its flow, and regularized the financial relationship between Rome and the provinces, rather than provoking fresh resentments with each new arbitrary exaction of tribute.[186] The measures of taxation in the reign of Augustus were determined by population census, with fixed quotas for each province.[187] Citizens of Rome and Italy paid indirect taxes, while direct taxes were exacted from the provinces.[187] Indirect taxes included a 4% tax on the price of slaves, a 1% tax on goods sold at auction, and a 5% tax on the inheritance of estates valued at over 100,000 sesterces by persons other than the next of kin.[187]

An equally important reform was the abolition of private tax farming, which was replaced by salaried civil service tax collectors. Private contractors that raised taxes had been the norm in the Republican era, and some had grown powerful enough to influence the amount of votes for politicians in Rome.[186] The tax farmers had gained great infamy for their depredations, as well as great private wealth, by winning the right to tax local areas.[186] Rome's revenue was the amount of the successful bids, and the tax farmers' profits consisted of any additional amounts they could forcibly wring from the populace with Rome's blessing. Lack of effective supervision, combined with tax farmers' desire to maximize their profits, had produced a system of arbitrary exactions that was often barbarously cruel to taxpayers, widely (and accurately) perceived as unfair, and very harmful to investment and the economy.

The use of Egypt's immense land rents to finance the Empire's operations resulted from Augustus's conquest of Egypt and the shift to a Roman form of government.[188] As it was effectively considered Augustus's private property rather than a province of the Empire, it became part of each succeeding emperor's patrimonium.[189] Instead of a legate or proconsul, Augustus installed a prefect from the equestrian class to administer Egypt and maintain its lucrative seaports; this position became the highest political achievement for any equestrian besides becoming Prefect of the Praetorian Guard.[190] The highly productive agricultural land of Egypt yielded enormous revenues that were available to Augustus and his successors to pay for public works and military expeditions,[188] as well as bread and circuses for the population of Rome.

Month of August

The month of August (Latin: Augustus) is named after Augustus; until his time it was called Sextilis (named so because it had been the sixth month of the original Roman calendar and the Latin word for six was sex). Commonly-repeated lore has it that August has 31 days because Augustus wanted his month to match the length of Julius Caesar's July, but this is an invention of the 13th century scholar Johannes de Sacrobosco. Sextilis in fact had 31 days before it was renamed, and it was not chosen for its length (see Julian calendar). According to a senatus consultum quoted by Macrobius, Sextilis was renamed to honour Augustus because several of the most significant events in his rise to power, culminating in the fall of Alexandria, fell in that month.[191]

Building projects

- Further information: Category:Augustan building projects

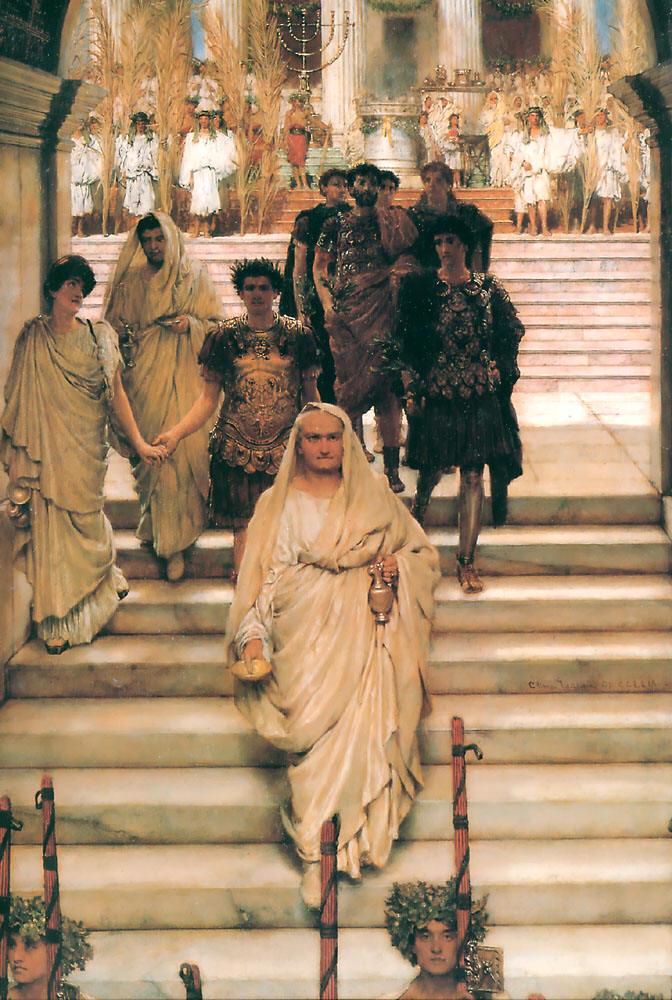

Close up on the sculpted detail of the

Ara Pacis (Altar of Peace), 13 BC to 9 BC.

On his deathbed, Augustus boasted "I found Rome of clay; I leave it to you of marble;" although there is some truth in the literal meaning of this, Cassius Dio asserts that it was a metaphor for the Empire's strength.[192] Marble could be found in buildings of Rome before Augustus, but it was not extensively used as a building material until the reign of Augustus.[193] Although this did not apply to the Subura slums, which were still as rickety and fire-prone as ever, he did leave a mark on the monumental topography of the centre and of the Campus Martius, with the Ara Pacis (Altar of Peace) and monumental sundial, whose central gnomon was an obelisk taken from Egypt.[194] The relief sculptures decorating the Ara Pacis visually augmented the written record of Augustus' triumphs in the Res Gestae.[195] Its reliefs depicted the imperial pageants of the praetorians, the Vestals, and the citizenry of Rome.[195] He also built the Temple of Caesar, the Baths of Agrippa, and the Forum of Augustus with its Temple of Mars Ultor. Other projects were either encouraged by him, such as the Theatre of Balbus, and Agrippa's construction of the Pantheon, or funded by him in the name of others, often relations (eg Portico of Octavia, Theatre of Marcellus). Even his Mausoleum of Augustus was built before his death to house members of his family.[196] To celebrate his victory at the Battle of Actium, the Arch of Augustus was built in 29 BC near the entrance of the Temple of Castor and Pollux, and widened in 19 BC to include a triple-arch design.[193] There are also many buildings outside of the city of Rome that bear Augustus' name and legacy, such as the Theatre of Merida in modern Spain, the Maison Carrée built at Nîmes in today's southern France, as well as the Trophy of Augustus at La Turbie, located near Monaco.

The Temple of Augustus and Livia in

Vienne, late 1st century BC.

After the death of Agrippa in 12 BC, a solution had to be found in maintaining Rome's water supply system. This came about because it was overseen by Agrippa when he served as aedile, and was even funded by him afterwards when he was a private citizen paying at his own expense.[175] In that year, Augustus arranged a system where the Senate designated three of its members as prime commissioners in charge of the water supply and to ensure that Rome's aqueducts did not fall into disrepair.[175] In the late Augustan era, the commission of five senators called the curatores locorum publicorum iudicandorum was put in charge of maintaining public buildings and temples of the state cult.[175] Augustus created the senatorial group of the curatores viarum for the upkeep of roads; this senatorial commission worked with local officials and contractors to organize regular repairs.[179]

The Corinthian order of architectural style originating from ancient Greece was the dominant architectural style in the age of Augustus and the imperial phase of Rome.[193] Suetonius once commented that Rome was unworthy of its status as an imperial capital, yet Augustus and Agrippa set out to dismantle this sentiment by transforming the appearance of Rome upon the classical Greek model.[193]

See also

Notes

^ a: Fully Imperator Caesar, Divi Filius, Augustus which means Imperator Caesar, Son of the Divus (Divus Julius), Augustus.

- ^ Some provinces were governed by the Senate.

- ^ CCAA, Erich S. Gruen, Augustus and the Making of the Principate, 35.

- ^ a b c Eck, 3.

- ^ a b c d Eck, 124.

- ^ Suetonius, Augustus 5–6 on-line text.

- ^ Suetonius, Augustus 1–4.

- ^ Rowell, 14.

- ^ Suetonius, Augustus 7

- ^ By Roman custom, one's status passed through one's father, not one's mother.

- ^ Chisholm, 23.

- ^ Suetonius, Augustus 4–8; Nicolaus of Damascus, Augustus 3.

- ^ Suetonius, Augustus 8.1; Quintilian, 12.6.1.

- ^ a b Suetonius, Augustus 8.1

- ^ Nicolaus of Damascus, Augustus 4.

- ^ a b c Rowell, 16.

- ^ Nicolaus of Damascus, Augustus 6.

- ^ Velleius Paterculus 2.59.3.

- ^ Suetonius, Julius 83.

- ^ a b c Eck, 9.

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 3.9–11.

- ^ His daughter Julia had died in 54 BC.

- ^ Rowell, 15.

- ^ Mackay, 160.

- ^ a b c d e f Eck, 10.

- ^ Suetonius, Augustus 68, 71.

- ^ a b Eck, 9–10.

- ^ a b Rowell, 19.

- ^ Rowell, 18.

- ^ CCAA, Walter Eder, Augustus and the Power of Tradition, 18.

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 3.11–12.

- ^ Chisholm, 24.

- ^ Chisholm, 27.

- ^ Rowell, 20.

- ^ Eck, 11.

- ^ Syme, 114–120.

- ^ Chisholm, 26.

- ^ Rowell, 30.

- ^ Eck, 11–12.

- ^ Rowell, 21.

- ^ Syme, 123–126.

- ^ a b c d Eck, 12.

- ^ a b c Rowell, 23.

- ^ Rowell, 24.

- ^ Chisholm, 29.

- ^ Chisholm, 30.

- ^ Rowell, 19–20.

- ^ Syme, 167.

- ^ Syme, 173–174

- ^ Scullard, 157.

- ^ Rowell, 26–27.

- ^ a b c Rowell, 27.

- ^ Chisholm, 32–33.

- ^ Eck, 14.

- ^ Rowell, 28.

- ^ Syme, 176–186.

- ^ Sear, David R. Common Legend Abbreviations On Roman Coins. Retrieved on 2007-08-24.

- ^ a b Eck, 15.

- ^ Scullard, 163.

- ^ a b c d Eck, 16.

- ^ Scullard, 164.

- ^ a b Eck, 17.

- ^ Syme, 202.

- ^ a b Eck, 17–18.

- ^ a b Eck, 18.

- ^ Eck, 18–19.

- ^ a b c d Eck, 19.

- ^ a b Rowell, 32.

- ^ a b c d e Eck, 20.

- ^ Scullard, 162

- ^ a b c d Eck 21.

- ^ a b c d CCAA, Walter Eder, Augustus and the Power of Tradition, 19.

- ^ a b Eck, 22.

- ^ Eck, 23.

- ^ Scullard, 163

- ^ a b Eck, 24.

- ^ a b Eck, 25.

- ^ Eck, 25–26.

- ^ a b c d e Eck, 26.

- ^ Scullard, 164

- ^ Eck, 26–27.

- ^ Eck, 27–28.

- ^ Eck, 29.

- ^ Eck, 29–30.

- ^ a b Eck, 30.

- ^ CCAA, Walter Eder, Augustus and the Power of Tradition, 20.

- ^ Eck, 31.

- ^ Eck, 32–34.

- ^ Eck, 34.

- ^ Eck, 34–35

- ^ CCAA, Walter Eder, Augustus and the Power of Tradition, 21–22.

- ^ Eck, 35.

- ^ CCAA, Walter Eder, Augustus and the Power of Tradition, 22.

- ^ a b c Eck, 37.

- ^ Eck, 38.

- ^ Eck, 38–39.

- ^ Eck, 39.

- ^ Green, 697.

- ^ Scullard, 171.

- ^ CCAA, Walter Eder, Augustus and the Power of Tradition, 21.

- ^ a b c d e Eck, 49.

- ^ CCAA, Erich S. Gruen, Augustus and the Making of the Principate, 34–35.

- ^ a b c d CCAA, 24–25.

- ^ a b CCAA, Erich S. Gruen, Augustus and the Making of the Principate, 38–39.

- ^ a b c d e Eck, 45.

- ^ Eck, 44–45.

- ^ Eck, 113.

- ^ a b Eck, 80.

- ^ Scullard, 211.

- ^ a b Eck, 46.

- ^ Scullard, 210.

- ^ a b CCAA, Erich S. Gruen, Augustus and the Making of the Principate, 34.

- ^ a b c Eck, 47.

- ^ a b c d CCAA, Walter Eder, Augustus and the Power of Tradition, 24.

- ^ Scullard, 211.

- ^ a b c d Eck, 50.

- ^ Eck, 149

- ^ CCAA, Walter Eder, Augustus and the Power of Tradition, 13.

- ^ a b c d CCAA, Walter Eder, Augustus and the Power of Tradition, 25.

- ^ Eck, 55.

- ^ Eck, 55–56.

- ^ a b c d e f g Eck, 56.

- ^ CCAA, Erich S. Gruen, Augustus and the Making of the Principate, 38.

- ^ a b c d e CCAA, Walter Eder, Augustus and the Power of Tradition, 26.

- ^ a b c Eck, 57.

- ^ a b CCAA, Erich S. Gruen, Augustus and the Making of the Principate, 36.

- ^ CCAA, Erich S. Gruen, Augustus and the Making of the Principate, 37.

- ^ Eck, 56–57.

- ^ Eck, 57–58.

- ^ Eck, 59.

- ^ a b CCAA, Walter Eder, Augustus and the Power of Tradition, 30.

- ^ Bunson, 80.

- ^ Bunson, 427.

- ^ a b Eck, 60.

- ^ a b c Eck, 61.

- ^ a b c Eck, 117.

- ^ Dio 54.1, 6, 10.

- ^ Eck, 78.

- ^ a b CCAA, Erich S. Gruen, Augustus and the Making of the Principate, 43.

- ^ Bowersock, p. 380. The date is provided by inscribed calendars; see also Augustus, Res Gestae 10.2. Dio 27.2 reports this under 13 BC, probably as the year in which Lepidus died (Bowersock, p. 383).

- ^ CCAA, Walter Eder, Augustus and the Power of Tradition, 28.

- ^ Mackay, 186.

- ^ Eck, 129.

- ^ a b c Eck, 93.

- ^ Eck, 95.

- ^ Eck, 95–96.

- ^ a b c d e f g Eck, 94.

- ^ a b Eck, 97.

- ^ Eck, 98.

- ^ Eck, 98–99.

- ^ a b Eck, 99.

- ^ a b c Bunson, 416.

- ^ a b c d e Eck, 96.

- ^ Rowell, 13.

- ^ Eck, 101–102.

- ^ Eck, 103.

- ^ Bunson, 417.

- ^ Bunson, 31.

- ^ a b CCAA, Erich S. Gruen, Augustus and the Making of the Principate, 50.

- ^ Eck, 114–115.

- ^ Eck, 115.

- ^ a b CCAA, Erich S. Gruen, Augustus and the Making of the Principate, 44.

- ^ a b Eck, 58.

- ^ a b c d Eck, 116.

- ^ a b CCAA, Erich S. Gruen, Augustus and the Making of the Principate, 46.

- ^ Eck, 117–118.

- ^ CCAA, Erich S. Gruen, Augustus and the Making of the Principate, 46–47.

- ^ Eck, 119.

- ^ Eck, 119–120.

- ^ a b CCAA, Erich S. Gruen, Augustus and the Making of the Principate, 49.

- ^ a b Eck, 123.

- ^ Suetonius, Augustus 101.4.

- ^ Eck, 1–2

- ^ Eck, 2.

- ^ Bunson, 47.

- ^ a b c d e Eck, 79.

- ^ Bunson, 345.

- ^ Eck, 85–87.

- ^ Eck, 86.

- ^ a b Eck, 81.

- ^ Chisholm, 122.

- ^ Bunson, 6.

- ^ Bunson, 341.

- ^ Bunson, 341–342.

- ^ a b c CCAA, Walter Eder, Augustus and the Power of Tradition, 23.

- ^ Tacitus, Annals I.3

- ^ a b c d Eck, 83–84.

- ^ a b c Bunson, 404.

- ^ a b Bunson, 144.

- ^ Bunson, 144–145.

- ^ Bunson, 145.

- ^ Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.12.35.

- ^ Dio 56.30.3

- ^ a b c d Bunson, 34.

- ^ Eck, 122.

- ^ a b Bunson, 32.

- ^ Eck, 118–121

References

- Everitt, Anthony (2006) Augustus: The Life of Rome's First Emperor. Random House Books. ISBN-10: 1400061288

- Bowersock, G. W. (1990). "The Pontificate of Augustus", in Kurt A. Raaflaub and Mark Toher (eds.): Between Republic and Empire: Interpretations of Augustus and his Principate. Berkeley: University of California Press, 380–394. ISBN 0-520-08447-0.

- Bunson, Matthew (1994). Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire. New York: Facts on File Inc. ISBN 0-8160-3182-7

- Chisholm, Kitty and John Ferguson. (1981). Rome: The Augustan Age; A Source Book. Oxford: Oxford University Press, in association with the Open University Press. ISBN 0-19-872108-0.

- Eck, Werner; translated by Deborah Lucas Schneider; new material by Sarolta A. Takács. (2003) The Age of Augustus. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing (hardcover, ISBN 0-631-22957-4; paperback, ISBN 0-631-22958-2).

- Eder, Walter. (2005). "Augustus and the Power of Tradition," in The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus (Cambridge Companions to the Ancient World), ed. Karl Galinsky, 13-32. Cambridge, MA; New York: Cambridge University Press (hardcover, ISBN 0-521-80796-4; paperback, ISBN 0-521-00393-8).

- Green, Peter (1990). Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age, Hellenistic Culture and Society. Berkeley, CA; Los Angeles; London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05611-6 (hbk.); ISBN 0-520-08349-0 (pbk.).

- Gruen, Erich S. (2005). "Augustus and the Making of the Principate," in The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus (Cambridge Companions to the Ancient World), ed. Karl Galinsky, 33-51. Cambridge, MA; New York: Cambridge University Press (hardcover, ISBN 0-521-80796-4; paperback, ISBN 0-521-00393-8).

- Mackay, Christopher S. (2004). Ancient Rome: A Military and Political History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521809185.

- Scullard, H. H. [1959] (1982). From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome from 133 B.C. to A.D. 68, 5th edition, London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-02527-3 (pbk.).

- Syme, Ronald (1939). The Roman Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280320-4 (pbk.). The classic revisionist study of Augustus

- Rowell, Henry Thompson. (1962). The Centers of Civilization Series: Volume 5; Rome in the Augustan Age. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-0956-4

Further reading

- Between Republic and Empire: Interpretations of Augustus and His Principate, edited by Kurt A. Raaflaub and Mark Toher. Berkeley; Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1993 (paperback, ISBN 0-520-08447-0).

- Everitt, Anthony. Augustus: The Life of Rome's First Emperor. New York: Random House, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 1-4000-6128-8). As The First Emperor: Caesar Augustus and the Triumph of Rome. London: John Murray, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 0719554942).

- Galinsky, Karl. Augustan Culture. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998 (paperback, ISBN 0-691-05890-3).

- Jones, A.H.M. "The Imperium of Augustus", The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 41, Parts 1 and 2. (1951), pp. 112–119.

- Jones, A.H.M. Augustus. London: Chatto & Windus, 1970 (paperback, ISBN 0-7011-1626-9).

- Osgood, Josiah. Caesar's Legacy: Civil War and the Emergence of the Roman Empire. New York: Cambridge University Press (USA), 2006 (hardback, ISBN 0-521-85582-9; paperback, ISBN 0-521-67177-9).

- Reinhold, Meyer. The Golden Age of Augustus (Aspects of Antiquity). Toronto, ON: Univ of Toronto Press, 1978 (hardcover, ISBN 0-89522-007-5; paperback, ISBN 0-89522-008-3).

- Southern, Pat. Augustus (Roman Imperial Biographies). New York: Routledge, 1998 (hardcover, ISBN 0-415-16631-4); 2001 (paperback, ISBN 0-415-25855-3).

- Zanker, Paul. The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus (Thomas Spencer Jerome Lectures). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1989 (hardcover, ISBN 0-472-10101-3); 1990 (paperback, ISBN 0-472-08124-1).

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to:

Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to:

Primary sources

Secondary source material