From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_crusade

Second Crusade

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| [hide] Crusades |

|---|

| First – People's – German – 1101 – Second – Wendish – Third – Livonian – 1197 – Fourth – Albigensian – Children's – Fifth – Prussian – Sixth – Seventh – Shepherds' – Eighth – Ninth – Aragonese – Alexandrian – Nicopolis – Northern – Hussite – Varna – Otranto |

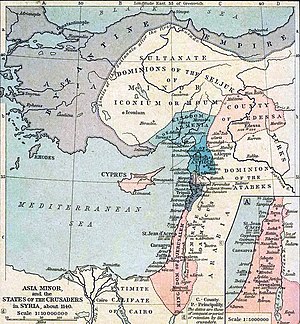

The Second Crusade (1145–1149) was the second major crusade launched from Europe, called in 1145 in response to the fall of the County of Edessa the previous year. Edessa was the first of the Crusader states to have been founded during the First Crusade (1095–1099), and was the first to fall. The Second Crusade was announced by Pope Eugene III, and was the first of the crusades to be led by European kings, namely Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany, with help from a number of other important European nobles. The armies of the two kings marched separately across Europe and were somewhat hindered by Byzantine emperor Manuel I Comnenus; after crossing Byzantine territory into Anatolia, both armies were separately defeated by the Seljuk Turks. Louis and Conrad and the remnants of their armies reached Jerusalem and, in 1148, participated in an ill-advised attack on Damascus. The crusade in the east was a failure for the crusaders and a great victory for the Muslims. It would ultimately lead to the fall of Jerusalem and the Third Crusade at the end of the 12th century.

The only success came outside of the Mediterranean, where Flemish, Frisian, Norman, English, Scottish, and some German crusaders, on the way by ship to the Holy Land, fortuitously stopped and helped the Portuguese in the capture of Lisbon in 1147. Some of them, who had departed earlier, helped capture other Santarém earlier in the same year. Later they also helped to conquer Sintra, Almada, Palmela and Setúbal, and were allowed to stay in the conquered lands, where they had offspring. Meanwhile, in Eastern Europe, the first of the Northern Crusades began with the intent of forcibly converting pagan tribes to Christianity, and these crusades would go on for centuries.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Background

After the First Crusade and the minor Crusade of 1101 there were three crusader states established in the east: the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Principality of Antioch, and the County of Edessa. A fourth, the County of Tripoli, was established in 1109. Edessa was the most northerly of these, and also the weakest and least populated; as such, it was subject to frequent attacks from the surrounding Muslim states ruled by the Ortoqids, Danishmends, and Seljuk Turks. Count Baldwin II and future count Joscelin of Courtenay were taken captive after their defeat at the Battle of Harran in 1104. Baldwin and Joscelin were both captured a second time in 1122, and although Edessa recovered somewhat after the Battle of Azaz in 1125, Joscelin was killed in battle in 1131. His successor Joscelin II was forced into an alliance with the Byzantine Empire, but in 1143 both the Byzantine emperor John II Comnenus and the King of Jerusalem Fulk of Anjou died. Joscelin had also quarreled with the Count of Tripoli and the Prince of Antioch, leaving Edessa with no powerful allies. Meanwhile, the Seljuk Zengi, Atabeg of Mosul, had added Aleppo to his rule in 1128. Aleppo was the key to power in Syria, contested between the rulers of Mosul and Damascus. Both Zengi and King Baldwin II turned their attention towards Damascus; Baldwin was defeated outside the city in 1129. Damascus, ruled by the Burid Dynasty, later allied with King Fulk when Zengi besieged the city in 1139 and 1140; the alliance was negotiated by the chronicler Usamah ibn Munqidh.

In late 1144, Joscelin II allied with the Ortoqids and marched out of Edessa with almost his entire army to support the Ortoqid Kara Aslan against Aleppo. Zengi, already seeking to take advantage of Fulk's death in 1143, hurried north to besiege Edessa, which fell to him after a month on December 24, 1144. Manasses of Hierges, Philip of Milly and others were sent from Jerusalem to assist, but arrived too late. Joscelin II continued to rule the remnants of the county from Turbessel, but little by little the rest of the territory was captured or sold to the Byzantines. Zengi himself was praised throughout Islam as "defender of the faith" and al-Malik al-Mansur, "the victorious king". He did not pursue an attack on the remaining territory of Edessa, or the Principality of Antioch, as was feared; events in Mosul compelled him to return home, and he once again set his sights on Damascus. However, he was assassinated by a slave in 1146 and was succeeded in Aleppo by his son Nur ad-Din. Joscelin attempted to take back Edessa following Zengi's murder, but Nur ad-Din defeated him in November of 1146.

[edit] Reaction in the west

The news of the fall of Edessa was brought back to Europe first by pilgrims early in 1145, and then by embassies from Antioch, Jerusalem, and Armenia. Bishop Hugh of Jabala reported the news to Pope Eugene III, who issued the bull Quantum praedecessores on December 1 of that year, calling for a second crusade. Hugh also told the Pope of an eastern Christian king, who, it was hoped, would bring relief to the crusader states: this is the first documented mention of Prester John. Eugene did not control Rome and lived instead at Viterbo, but nevertheless the crusade was meant to be more organized and centrally controlled than the First Crusade: certain preachers would be approved by the pope, the armies would be led by the strongest kings of Europe, and a route would be planned beforehand. The initial response to the new crusade bull was poor, and it in fact had to be reissued when it was clear that Louis VII would be taking part in the expedition. Louis VII of France had also been considering a new expedition independently of the Pope, which he announced to his Christmas court at Bourges in 1145. It is debatable whether Louis was planning a crusade of his own or in fact a pilgrimage, as he wanted to fulfil a vow made by his brother Philip to go to the Holy Land, as he had been prevented by death. It is probable that Louis had made this decision independently of hearing about Quantum Praedecessores.In any case, Abbot Suger and other nobles were not in favour of Louis' plans, as he would potentially be gone from the kingdom for several years. Louis consulted Bernard of Clairvaux, who referred him back to Eugene. Now Louis would have definitely heard about the papal bull, and Eugene enthusiastically supported Louis' crusade. The bull was reissued on March 1, 1146, and Eugene authorized Bernard to preach the news throughout France.

[edit] Bernard of Clairvaux preaches the crusade

There had been virtually no popular enthusiasm for the crusade as there had been in 1095 and 1096. However, St. Bernard, one of the most famous and respected men of Christendom at the time, found it expedient to dwell upon the taking of the cross as a potent means of gaining absolution for sin and attaining grace. On March 31, with Louis present, he preached to an enormous crowd in a field at Vézelay. Bernard, "the honey-tongued teacher" worked his magic of oration, men rose up and yelled "Crosses, give us Crosses!" and they supposedly ran out of cloth to make crosses; to make more Bernard is said to have given his own outer garments to be cut up. Unlike the First Crusade, the new venture attracted Royalty, such as Eleanor of Aquitaine, then Queen of France; Thierry of Alsace, Count of Flanders; Henry, the future Count of Champagne; Louis’ brother Robert I of Dreux; Alphonse I of Toulouse; William II of Nevers; William de Warenne, 3rd Earl of Surrey; Hugh VII of Lusignan; and numerous other nobles and bishops. But an even greater show of support came from the common people. St. Bernard wrote to the Pope a few days afterwards: "I opened my mouth; I spoke; and at once the Crusaders have multiplied to infinity. Villages and towns are now deserted. You will scarcely find one man for every seven women. Everywhere you see widows whose husbands are still alive".

It was decided that the crusaders would depart in one year, during which time they would make preparations and lay out a route to the Holy Land. Louis and Eugene received support from those rulers whose lands they would have to cross: Geza of Hungary, Roger II of Sicily, and Byzantine emperor Manuel I Comnenus, although Manuel wanted the crusaders to swear an oath of fealty to him, just as his grandfather Alexius I Comnenus had demanded.

Meanwhile St. Bernard continued to preach in Burgundy, Lorraine and Flanders. As in the First Crusade, the preaching inadvertently led to attacks on Jews; a fanatical French monk named Rudolf was apparently inspiring massacres of Jews in the Rhineland, Cologne, Mainz, Worms, and Speyer, with Rudolf claiming Jews were not contributing financially to the rescue of the Holy Land. St. Bernard, the Archbishop of Cologne and the Archbishop of Mainz were vehemently opposed to these attacks, and so St. Bernard traveled from Flanders to Germany to deal with the problem, and for the most part Bernard convinced Rudolf’s audience to follow him instead. Bernard then found Rudolf in Mainz and was able to silence him, returning him to his monastery.

While still in Germany, St. Bernard also preached to Conrad III of Germany in November of 1146, but as Conrad was not interested in participating himself, Bernard continued onwards to preach in southern Germany and Switzerland. However, on the way back in December, he stopped at Speyer, where, in the presence of Conrad, he delivered an emotional sermon in which he took the role of Christ and asked what more he could do for the emperor. "Man", he cried, "what ought I to have done for you that I have not done?" Conrad could no longer resist and joined the crusade with many of his nobles, including Frederick II, Duke of Swabia. Just as at Vézelay earlier, many common people also took up the cause in Germany.

The Pope also authorized a Crusade in Spain, although the war against the Moors had been going on for some time already. He granted Alfonso VII of Castile the same indulgence he had given to the French crusaders, and like Pope Urban II had done in 1095, urged the Spanish to fight on their own territory rather than joining the crusade to the east. He authorized Marseille, Pisa, Genoa, and other cities to fight in Spain as well, but elsewhere urged the Italians, such as Amadeus III of Savoy, to go to the east. Eugene did not want Conrad to participate, hoping instead that he would give imperial support to his own claims on the papacy, but he did not forbid him outright from leaving. As well as this, Eugene III also authorized a crusade in the Germanic lands against the Wends, who were pagan. Wars had been going on for some time between the Germans and Wends, and it took the persuasion of Bernard to allow indulgences to be issued for the Wendish Crusade. the expedition itself was not of traditional crusading nature, as it was an expansive one against pagans rather than Muslims, and was not related to the protection of the Holy Land. The Second Crusade therefore saw an interesting development in new arenas for crusading.

[edit] Preparations

On February 16, 1147, the French crusaders met at Étampes to discuss their route. The Germans had already decided to travel overland through Hungary, as Roger II was an enemy of Conrad and the sea route was politically impractical. Many of the French nobles distrusted the land route, which would take them through the Byzantine Empire, the reputation of which still suffered from the accounts of the First Crusaders. Nevertheless it was decided to follow Conrad, and to set out on June 15. Roger II was offended and refused to participate any longer. In France, Abbot Suger and Count William of Nevers were elected as regents while the king would be on crusade.

In Germany, further preaching was done by Adam of Ebrach, and Otto of Freising also took the cross. On March 13 at Frankfurt, Conrad’s son Frederick was elected king, under the regency of Henry, Archbishop of Mainz. The Germans planned to set out in May and meet the French in Constantinople. During this meeting, other German princes extended the idea of a crusade to the Slavic tribes living to the northeast of the Holy Roman Empire, and were authorized by Bernard to launch a crusade against them. On April 13 Eugene confirmed this crusade, comparing to the crusades in Spain and Palestine. Thus in 1147 the Wendish Crusade was also born.

[edit] The crusade in Spain and Portugal

In mid-May the first contingents left from England, consisting of Flemish, Frisian, Norman, English, Scottish, and some German crusaders. No prince or king led this part of the crusade; England at the time was in the midst of The Anarchy. They arrived at Porto at June, and were convinced by the bishop to continue to Lisbon, to which King Afonso I of Portugal had already gone when he heard a crusader fleet was on its way. Since the Iberian crusade was already sanctioned by the pope, and they would still be fighting Muslims, the crusaders agreed. The siege of Lisbon began on July 1 and lasted until October 24 when the city fell to the crusaders, who thoroughly plundered it before handing it over to King Afonso. Some of the crusaders settled in the newly captured city, and Gilbert of Hastings was elected bishop, but most of the fleet continued to the east in February 1148. Almost at the same time, the Spanish under Alfonso VII of Castile and Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Barcelona and others captured Almería. In 1148 and 1149 they also captured Tortosa, Fraga, and Lerida.

[edit] German departure

The German crusaders, consisting of Franconians, Bavarians, and Swabians, left by land, also in May 1147, accompanied by the papal legate and cardinal Theodwin. Ottokar III of Styria joined Conrad at Vienna, and Conrad's enemy Geza II of Hungary was finally convinced to let them pass through unharmed. When the army arrived in Byzantine territory, Manuel feared they were going to attack him, and Byzantine troops were posted to ensure that there was no trouble. There was a brief skirmish with some of the more unruly Germans near Philippopolis and in Adrianople, where the Byzantine general Prosouch fought with Conrad’s nephew, the future emperor Frederick. To make things worse, some of the German soldiers were killed in a flood at the beginning of September. On September 10, however, they arrived at Constantinople, where relations with Manuel were poor and the Germans were convinced to cross into Asia Minor as quickly as possible. Manuel wanted Conrad to leave some of his troops behind, to assist Manuel in defending against attacks from Roger II, who had taken the opportunity to plunder the cities of Greece, but Conrad did not agree, despite being a fellow enemy of Roger.

In Asia Minor, Conrad decided not to wait for the French, and marched towards Iconium, capital of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rüm. Conrad split his army into two divisions, one of these was destroyed by the Seljuks on October 25, 1147 at the second battle of Dorylaeum. The Turks used their typical tactic of pretending to retreat, and then returning to attack the small force of German cavalry which had separated from the main army to chase them. Conrad began a slow retreat back to Constantinople, and his army was harassed daily by the Turks, who attacked stragglers and defeated the rearguard. Even Conrad was wounded in a skirmish with them. The other division, led by Otto of Freising, had marched south to the Mediterranean coast and was similarly defeated early in 1148.

[edit] French departure

The French crusaders departed from Metz in June, led by Louis, Thierry of Alsace, Renaut I of Bar, Amadeus III of Savoy and his half-brother William V of Montferrat, William VII of Auvergne, and others, along with armies from Lorraine, Brittany, Burgundy, and Aquitaine. A force from Provence, led by Alphonse of Toulouse, chose to wait until August, and to cross by sea. At Worms, Louis joined with crusaders from Normandy and England. They followed Conrad’s route fairly peacefully, although Louis came into conflict with Geza of Hungary when Geza discovered Louis had allowed an attempted Hungarian usurper to join his army.

Relations within Byzantine territory were also poor, and the Lorrainers, who had marched ahead of the rest of the French, also came into conflict with the slower Germans whom they met on the way. Since the original negotiations between Louis and Manuel, Manuel had broken off his military campaign against the Sultanate of Rüm, signing a truce with his enemy Sultan Mesud I. This was done so that Manuel would be free to concentrate on defending his empire from the Crusaders, who had gained a reputation for theft and treachery since the First Crusade and were widely suspected of harbouring sinister designs on Constantinople. Nevertheless, Manuel's relations with the French army were somewhat better than with the Germans, and Louis was entertained lavishly in Constantinople. Some of the French were outraged by Manuel's truce with the Seljuks and called for an attack on Constantinople, but they were restrained by the papal legates.

When the armies from Savoy, Auvergne, and Montferrat joined Louis in Constantinople, having taken the land route through Italy and crossing from Brindisi to Durazzo, the entire army was shipped across the Bosporus to Asia Minor. In the tradition set by his grandfather Alexios I, Manuel had the French swear to return to the Empire any territory they captured. They were encouraged by rumours that the Germans had captured Iconium, but Manuel refused to give Louis any Byzantine troops. Byzantium had just been invaded by Roger II of Sicily, and all of Manuel's army was needed in the Balkans. Both the Germans and French therefore entered Asia without any Byzantine assistance, unlike the armies of the First Crusade.

The French met the remnants of Conrad's army at Nicaea, and Conrad joined Louis' force. They followed Otto of Freising's route along the Mediterranean coast, and they arrived at Ephesus in December, where they learned that the Turks were preparing to attack them. Manuel also sent ambassadors complaining about the pillaging and plundering that Louis had done along the way, and there was no guarantee that the Byzantines would assist them against the Turks. Meanwhile Conrad fell sick and returned to Constantinople, where Manuel attended to him personally, and Louis, paying no attention to the warnings of a Turkish attack, marched out from Ephesus.

The Turks were indeed waiting to attack, but in a small battle outside Ephesus, the French were victorious. They reached Laodicea early in January 1148, only a few days after Otto of Freising’s army had been destroyed in the same area. Resuming the march, the vanguard under Amadeus of Savoy became separated from the rest of the army, and Louis’ troops were routed by the Turks. Louis himself, according to Odo of Deuil, climbed a rock and was ignored by the Turks, who did not recognize him. The Turks did not bother to attack further and the French marched on to Adalia, continually harassed from afar by the Turks, who had also burned the land to prevent the French from replenishing their food, both for themselves and their horses. Louis wanted to continue by land, and it was decided to gather a fleet at Adalia and sail for Antioch. After being delayed for a month by storms, most of the promised ships did not arrive at all. Louis and his associates claimed the ships for themselves, while the rest of the army had to resume the long march to Antioch. The army was almost entirely destroyed, either by the Turks or by sickness.

[edit] Journey to Jerusalem

Louis eventually arrived in Antioch on March 19, after being delayed by storms; Amadeus of Savoy had died on Cyprus along the way. Louis was welcomed by Eleanor’s uncle Raymond of Poitiers. Raymond expected him to help defend against the Turks and to accompany him on an expedition against Aleppo, but Louis refused, preferring instead to finish his pilgrimage to Jerusalem rather than focus on the military aspect of the crusade. Eleanor enjoyed her stay, but her uncle wanted her to remain behind and divorce Louis if the king refused to help him. Louis quickly left Antioch for Tripoli. Meanwhile, Otto of Freising and the remnant of his troops arrived in Jerusalem early in April, and Conrad soon after, and Fulk, Patriarch of Jerusalem, was sent to invite Louis to join them. The fleet that had stopped at Lisbon arrived around this time, as well as the Provencals under Alphonse of Toulouse. Alphonse himself had died on the way to Jerusalem, supposedly poisoned by Raymond II of Tripoli, his nephew who feared his political aspirations in the county.

[edit] Council of Acre

In Jerusalem the focus of the crusade quickly changed to Damascus, the preferred target of King Baldwin III and the Knights Templar. Conrad was persuaded to take part in this expedition. When Louis arrived, the Haute Cour met at Acre on June 24. This was the most spectacular meeting of the Cour in its existence: Conrad, Otto, Henry II of Austria, future emperor Frederick I Barbarossa (at the time Duke of Swabia), and William V of Montferrat represented the Holy Roman Empire; Louis, Alphonse's son Bertrand, Thierry of Alsace, and various other ecclesiastical and secular lords represented the French; and from Jerusalem King Baldwin, Queen Melisende, Patriarch Fulk, Robert of Craon (master of the Knights Templar), Raymond du Puy de Provence (master of the Knights Hospitaller), Manasses of Hierges (constable of Jerusalem), Humphrey II of Toron, Philip of Milly, Walter Grenier, and Barisan of Ibelin were among those present. Notably, no one from Antioch, Tripoli, or the former County of Edessa attended. Some of the French considered their pilgrimage completed, and wanted to return home; some of the barons native to Jerusalem pointed out that it would be unwise to attack Damascus, their ally against the Zengid dynasty. Conrad, Louis, and Baldwin insisted, however, and in July an army assembled at Tiberias.

[edit] Siege of Damascus

- Main article: Siege of Damascus

The crusaders decided to attack Damascus from the west, where orchards would provide them with a constant food supply. They arrived on July 23, with the army of Jerusalem in the vanguard, followed by Louis and then Conrad in the rearguard. The Muslims were prepared for the attack and constantly attacked the army advancing through the orchards. The crusaders managed to fight their way through and chase the defenders back across the Barada River and into Damascus; having arrived outside the walls of the city, they immediately put it to siege. Damascus had sought help from Saif ad-Din Ghazi I of Aleppo and Nur ad-Din of Mosul, and the vizier, Mu'in ad-Din Unur, led an unsuccessful attack on the crusader camp. There were conflicts in both camps: Unur could not trust Saif ad-Din or Nur ad-Din from conquering the city entirely if they offered help; and the crusaders could not agree about who would receive the city if they captured it. On July 27 the crusaders decided to move to the eastern side of the city, which was less heavily fortified but had much less food and water. Nur ad-Din had by now arrived and it was impossible to return to their better position. First Conrad, then the rest of the army, decided to retreat back to Jerusalem.

[edit] Aftermath

All sides felt betrayed by the others. A new plan was made to attack Ascalon, and Conrad took his troops there, but no further help arrived, due to the lack of trust that had resulted from the failed siege. The expedition to Ascalon was abandoned, and Conrad returned to Constantinople to further his alliance with Manuel, while Louis remained behind in Jerusalem until 1149. Back in Europe, Bernard of Clairvaux was also humiliated, and when his attempt to call a new crusade failed, he tried to disassociate himself from the fiasco of the Second Crusade altogether. He died in 1153.

The siege of Damascus had disastrous long-term consequences for Jerusalem: Damascus no longer trusted the crusader kingdom, and the city was handed over to Nur ad-Din in 1154. Baldwin III finally seized Ascalon in 1153, which brought Egypt into the sphere of conflict. Jerusalem was able to make further advances into Egypt, briefly occupying Cairo in the 1160s. However, relations with the Byzantine Empire were mixed, and reinforcements from the west were sparse after the disaster of the Second Crusade. King Amalric I of Jerusalem allied with the Byzantines and participated in a combined invasion of Egypt in 1169, but the expedition ultimately failed. In 1171, Saladin, nephew of one of Nur ad-Din's generals, was proclaimed Sultan of Egypt, uniting Egypt and Syria and completely surrounding the crusader kingdom. Meanwhile the Byzantine alliance ended with the death of emperor Manuel I in 1180, and in 1187 Jerusalem capitulated to Saladin. His forces then spread north to capture all but the capital cities of the Crusader States, precipitating the Third Crusade.

[edit] References

- Primary sources

- Anonymous. De expugniatione Lyxbonensi. The Conquest of Lisbon. Edited and translated by Charles Wendell David. Columbia University Press, 1936.

- Odo of Deuil. De profectione Ludovici VII in orientem. Edited and translated by Virginia Gingerick Berry. Columbia University Press, 1948.

- Otto of Freising. Gesta Friderici I Imperatoris. The Deeds of Frederick Barbarossa. Edited and translated by Charles Christopher Mierow. Columbia University Press, 1953.

- The Damascus Chronicle of the Crusaders, extracted and translated from the Chronicle of Ibn al-Qalanisi. Edited and translated by H. A. R. Gibb. London, 1932.

- William of Tyre. A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea. Edited and translated by E. A. Babcock and A. C. Krey. Columbia University Press, 1943.

- O City of Byzantium, Annals of Niketas Choniatēs, trans. Harry J. Magoulias. Wayne State University Press, 1984.

- John Cinnamus, Deeds of John and Manuel Comnenus, trans. Charles M. Brand. Columbia University Press, 1976.

- Secondary sources

- Michael Gervers, ed. The Second Crusade and the Cistercians. St. Martin's Press, 1992.

- Jonathan Phillips and Martin Hoch, eds. The Second Crusade: Scope and Consequences. Manchester University Press, 2001.

- Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades, vol. II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100–1187. Cambridge University Press, 1952.

- Kenneth Setton, ed. A History of the Crusades, vol. I. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1958 (available online).

[edit] External links

- The Second Crusade and Aftermath at the Internet Medieval Sourcebook

- Quantum praedecessores from the Patrologia Latina (in Latin)